One of the many advantages of using dbt instead of transforming your data directly in your data warehouse is the extensive set of options you have to assess data quality. Testing your data can make you more confident that your raw data is accurate (you don't have any issues in the extract and load portion of your pipeline) and that your transformations are working as expected (you're not blowing up joins or failing to properly clean your data).

How do tests work?

Tests are just SQL select statements set up to return any rows in a source or model that violate a particular data quality assertion. Pay careful attention to that: they're set up to return the bad data. If no rows are returned, that means the test has passed.

Below you can see the actual SQL that's run against the warehouse when a not_null test on a column <column> in a model or source located at <database>.<schema>.<model/source> is configured. dbt will error if any rows are returned by the query (because they have null values for the given column). You can view this SQL when you run a command to execute a test in dbt Platform by clicking on the executed test and selecting the debug logs.

select

count(*) as failures,

count(*) != 0 as should_warn,

count(*) != 0 as should_error

from (

select <column>

from <database>.<schema>.<model/source>

where <column> is null

)What kinds of tests are there?

Generic tests

dbt includes four generic tests out of the box:

- unique - The given column has no duplicated values

- not_null - The given column has no null values

- accepted_values - The given column's values all fall within the provided list of values

- relationships - The given column's values all exist within another stipulated column in a separate model/source (also known as referential integrity)

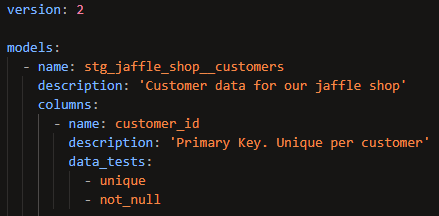

You can apply those generic tests to a model within a YAML file. Here's an example in which the unique and not_null tests are applied to the column customer_id in the model stg_jaffle_shop__customers:

It's best practice to apply these two tests to primary keys, since you want to ensure that they are truly unique and aren't missing any data.

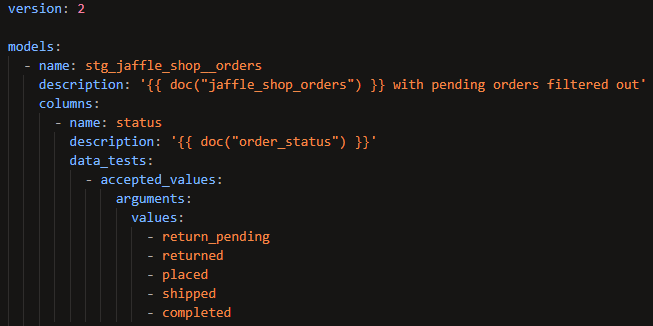

Here's another example in which an accepted_values test is applied to the status column in the stg_jaffle_shop__orders model:

If any values other than 'return_pending', 'returned', 'placed', 'shipped', or 'completed' are found in the status column, this test will error.

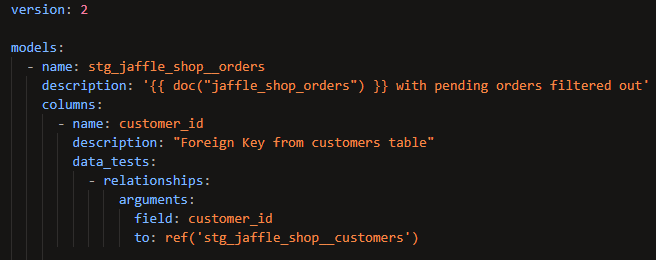

Below is an example of a relationships test:

This test asserts that every value in the customer_id column in the stg_jaffle_shop__orders model also exists in the column customer_id in the stg_jaffle_shop__customers model. In other words, everyone who's placed an order is listed in the table of customers. This is the most common application of the relationships test – checking that a foreign key has analogous values in the table in which it's a primary key.

Custom generic tests

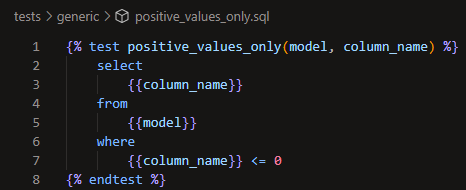

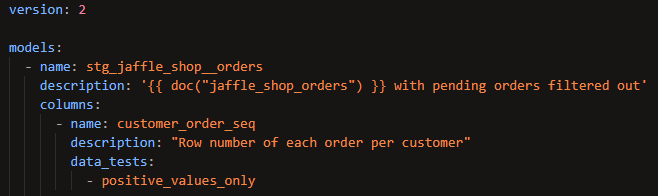

If the four provided tests aren't enough, you can create your own using Jinja in a SQL file in the tests folder of your repository. Here's an example of a test that asserts that there are only positive values in the given column:

In this case, using model and column_name as the arguments will automatically insert the name of the model and column into the test when it runs so you don't need to pass them as arguments when you call that test in a YAML file. You'll need to pass other arguments that you define that don't use special reserved words like those. Here's how you'd apply that test to a column in a YAML file:

Notice how similar it looks to applying one of the in-built generic tests – it's the same thing but with the added flexibility of being able to customize your assertions using Jinja.

Singular tests

In all of the above examples, the tests being used are ones that could realistically apply in many different situations. That might not always be the case, though. You might have a very specific condition that applies only to a single model. In that case, you might want to consider a singular test.

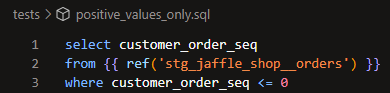

Similar to custom generic tests, these are fully customizable and need to be included as SQL files in the tests folder of your repository. The difference is that they explicitly reference one or more models/sources in your project. Here's how you could apply the same positive_values_only test as a singular test instead of a generic one:

So which should you use? In this case, I think it makes more sense to apply this as a generic test. Checking if values are positive could realistically apply to multiple columns or models/sources. Since this singular test specifically references stg_jaffle_shop__orders, you'd need to create another singular test if you wanted to apply the same assertion to a different model. By creating a generic test, you can easily apply the same assertion in as many places as you want. If this had been a very niche condition that's unlikely to apply to any other columns or models/sources, it might be preferable to use a singular test instead.

Tests in packages

This is another big advantage of dbt – there are tons of packages you can easily install that give you access to functionality you'd otherwise have to build out yourself. Tests are just one example of the kind of additional functionality you can get through packages. dbt utils and dbt expectations are two good examples of packages with useful generic tests included.

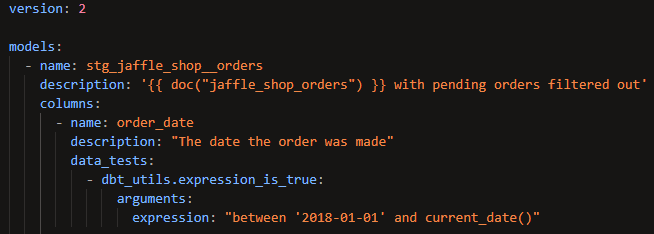

Here's an example in which the expression_is_true generic test from dbt utils is used to check that order_date from stg_jaffle_shop__orders falls within the expected range:

The only thing you have to do that isn't necessary when applying a generic test you created yourself is to prepend the test name with the name of the package (hence the 'dbt_utils.').

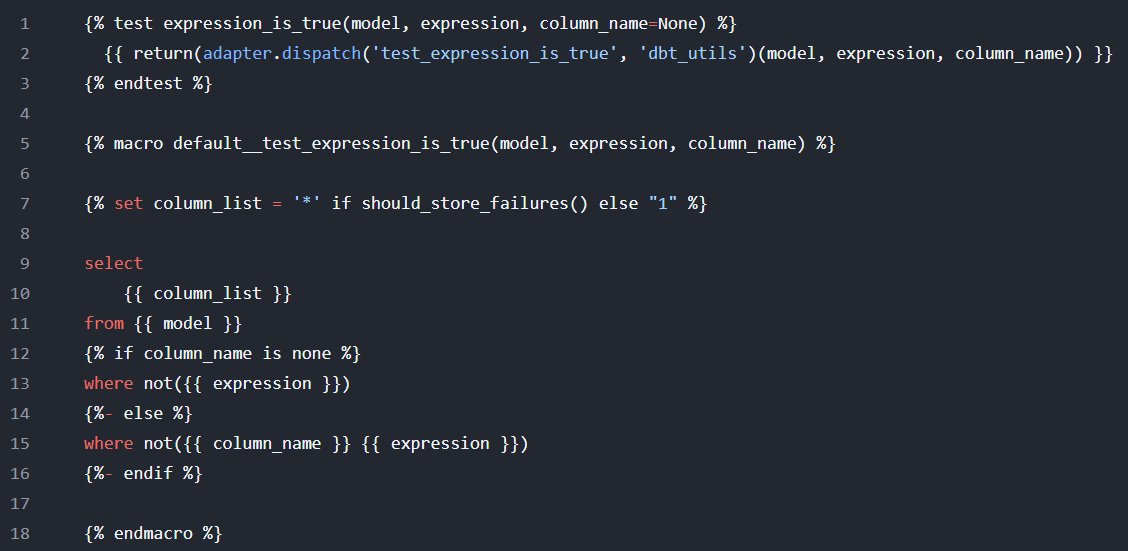

If you'd like to see the definition of the test, you can view the GitHub repo for the package (which you can find in the package hub page that I linked above). This is a more advanced test than the ones shown above. It allows you to write SQL as an argument. If that SQL statement evaluates to false, the test will fail. Here's the code used to create the test (which also involves defining a macro):

Unit tests

These are different from the other types of tests. If you want to be really specific, the others are referred to as data tests. When you want to apply a generic test, you'll write 'data_tests:' in the YAML code (this used to just be 'tests:' until the introduction of unit tests). The key distinction is that data tests are checking that the data itself conforms to particular expectations. Unit tests (one of many examples of dbt bringing a software engineering practice to the data world) involve testing your code itself, with no references being made to the actual data in the model.

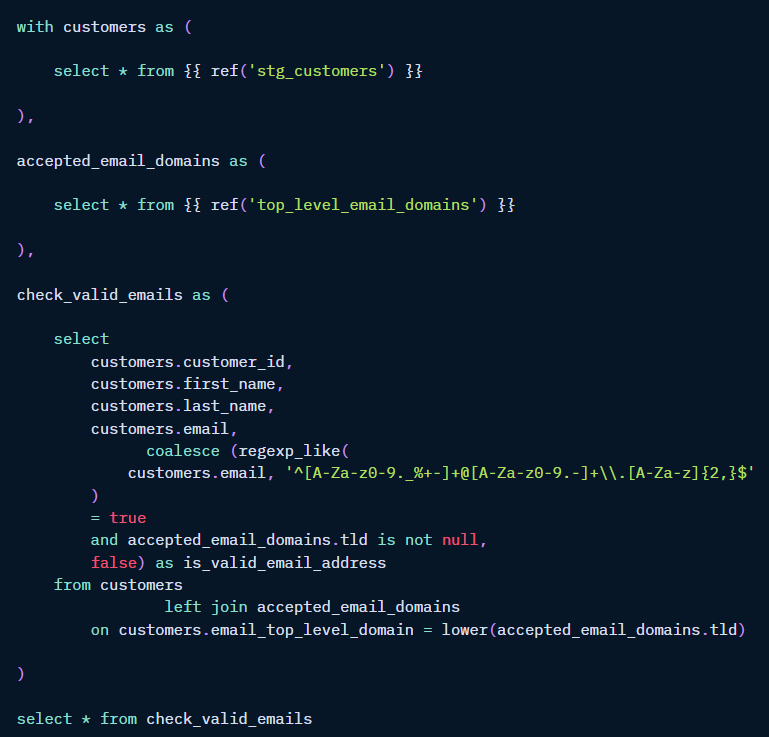

Here's an example of a unit test used in the official dbt documentation for them. This is the definition of a model called dim_customers:

The is_valid_email_address boolean field involves some complex regex logic. Validating that that code is doing what it's intended to do will involve testing certain edge cases that may or may not appear in the data.

A good solution is a unit test that allows you to manually define the rows of data and the corresponding values of is_valid_email_address. dbt will apply your code to those rows of data and compare the results with the expected values you provided, erroring if they don't match.

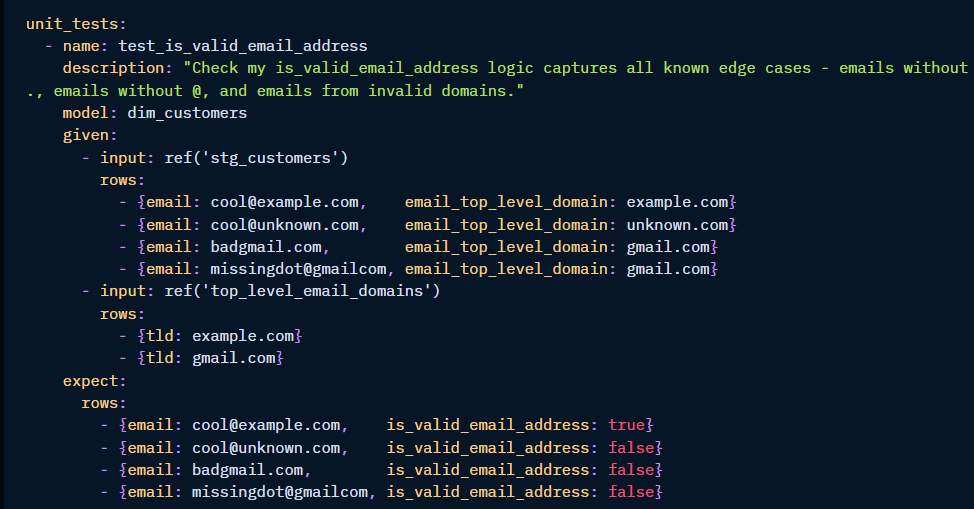

Here's how you can define that unit test in a YAML file:

Here's what each piece is doing:

- 'model:' tells dbt which model's code it needs to run to perform the unit test

- 'given:' allows you to manually insert fake data that will be used in the test

- 'expect:' where you insert the correct values of is_valid_email_address for each row of fake data that you've provided

Since unit tests depend exclusively on your code, there's no need to run them unless your code is changing. That means it's not necessary to run them each time your project runs in production. It suffices to run them in development (when your code is still a work-in-progress) and during continuous integration jobs (to ensure that changes to your code haven't broken your unit tests).